I’m an old queen. Whatever you’re thinking that’s probably not it. In 2013 I competed in the annual Eugene SLUG Queen Competitionand won. I am Old Queen Professor Doctor Mildred Slugwak Dresselhaus[1], named in honor of the late great Queen of Carbon Nanonscience, Millie Dresselhaus[2]. It wasn’t my first time competing for the crown, you see, I tried in 2012 and I failed. We put up a valiant fight, bribing the old queens with the gift of SCIENCE! for the masses [3]. It was a close thing, but I was edged out by Queen Sadie Slimey Stitches and her Naughty Knitters.

It’s not my defeat in 2012 that makes me cringe though. It’s what came after winning. SLUG Queens started out as a sort of kitschy joke, but sometime in the early aughts the queens upped the ante and started advocating for causes. It is now traditional for the Raining Queen [4] to hold a gala fundraiser for her chosen cause. I was the first (and so far only) Science Slug Queen and I was raising awareness and money for the SPICE program. For months I worked on beautiful posters, collecting donations, getting out word of mouth on social media, and planning a night full of fun science activities. The gala was lovely . . . and about 25 people came for a space designed to hold 200. Ouch! The only thing that save the event from taking a loss was the heroic MC work of Old Queen Bananita who cajoled and amused the few folks on hand to buy enough stuff from our auction to get us (barely) into the black.

I made lots of mistakes along the way to my very public face-plant. Just thinking about it makes my eyes go squinchy. I keep the lovely poster made by my friend and co-conspirator Pinky (aka Jen Weber) in my office as a reminder. Failure is never far away.

I am a motivational researcher. Understanding the impacts of failure is key to understanding all sorts of aspects of motivation (identity and self-efficacy being two big ones). I spend a lot of time proclaiming the value of failure in learning, but I’m gonna be straight with you, failing sucks. It’s no fun to take a risk and fall flat on your face. No one likes to feel incompetent or foolish, especially in front of witnesses. The desire to avoid this kind of embarrassment can lead to some pretty impressive avoidance strategies. Adolescents and youth in particular are keenly tuned in to the dangers of social embarrassment. Many pre-fossils like myself have any number of embarrassing stories we can trot out for amusement now that we are at a remove (and I do think being able to laugh at your own mistakes is a sign of maturity), but I bet most of us also have a few we do not care to share, even decades later (I know I do).

Science, by its very nature, is a process of failure. Failure is not merely an option in scientific inquiry, it’s a prerequisite to even the most humble success. Consider the scientific method:

Ask a question

(admit you don’t know something)

Investigate

(learn more, because you don’t know enough)

Hypothesize

(take a risk by making a guess)

Design

(try to figure out how to answer your question)

Test

(collect some data and hope it makes sense)

Analyze

(can you figure out what you did actually means?)

Share

(tell the world all the ways in which you were wrong, and if you are very lucky the one or few things you got kind of right)

Scientists become old friends with failure. More like frenemies who don not actually like each other and engage in a lot of one-upmanship. One of the ways scientist do this is by contextualizing failure and making room for it in the process. Scientists know they aren’t going to get everything right the first time, they build a learning curve into their experiments, reach out to experts for advice, and collaborate with people who have experience. They document their failures and try again, hopefully having learned something that will help with future attempts.

The scientific community is actually experiencing a problem right now. There’s a heavy bias in the publishing of data only to report positive results. Negative results (aka failures) rarely make it into the literature which is resulting in duplication of effort and an incomplete picture of what is actually known. After all, if you’re trying an experiment, wouldn’t you like to know if someone else did it before and found it doesn’t work? Often, when learning new things there is value in repeating something that’s been done before, even if it doesn’t work. Just as often it’s just a big waste of your time. Why do that? But our fear of failure and collective bias toward success is creating a problem.

Failure becomes particularly problematic for out-group members. If you read my Nerding While Female post, then you have heard at least a little of how women’s membership in male dominated identity groups such as sports fan, cultural geek, and science are often subject to heavy gatekeeping and policing. Any time an individual is not perceived as a natural member of a group this extra barrier to membership identity can be found. For in group members, failure is just a small set back. For outgroup members failure is yet another symbol of not belonging. Couple this with the fixed mindset that often manifests in out-group members seeking entry and stereotype threat (illustrated beautifully in this comic) and failure becomes a serious threat to integrating a science identity for anyone who does not fit the scientist stereotype.

There is hope though. There are ways to make failure into an ally.

First and foremost educators and mentors can help students contextualize failure. Often when students are first introduced to the scientific method they think the goal is the come up with the correct hypothesis and prove it. This can make science projects a crushing experience when they should be an exciting process of discovery. When teaching science fair projects through SPICE, we always emphasize that a hypothesis is just your best guess and that the point of the process is to learn something new. There is no “right” answer. Doing it right means being thoughtful, observant, and analytic. The most valuable thing any scientist can do is find and proudly share her mistakes and incorrect assumptions. Mature scientists spend far more time on the shortcomings of their work than on the successes [5]. Understanding what went wrong is so much more valuable than getting everything perfectly right the first time.

Failure is only true failure if you didn’t learn anything.

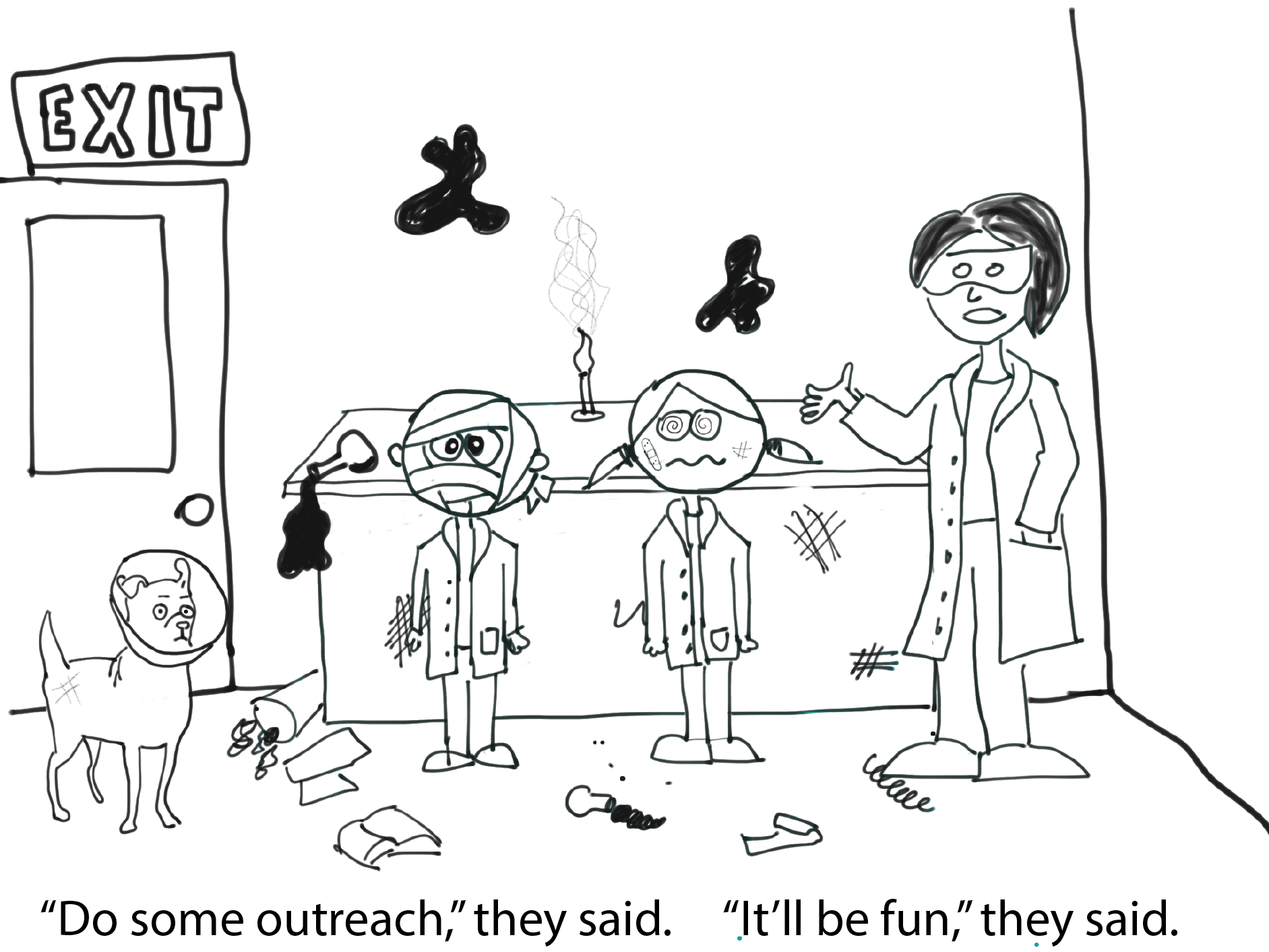

In SPICE we tell our girls that failure, is not only an option, but a prerequisite for any scientific endeavor. Perseverance, analysis, and a good sense of humor when it comes to your own mistakes are the most important skills for being a scientist.

Use failure as a sharing opportunity. Whenever we carry out a complex of difficult experiment in SPICE I ask for volunteers who want to share their failures and what they learned from them. Hearing that others have flopped is a powerful learning experience. My favorite times are when students learn from the mistakes of others. Once at an engineering Saturday workshop a team shared how explained how they had tried something a little different with their structure that had not worked and another girl piped in, “I saw what they did and I thought it was really cool, but it wasn’t working. So I tried it with a different setup and it worked great. I would never have figured it out if I hadn’t seen their idea.”

When you provide a space for sharing failure it helps others learn from your mistakes and creates a shared sense of what it means to be a learner who fails. Students who started out with hanging heads or frustrated glares are soon laughing at their peers stories and sharing their own face plants.

“I can tell you one, thing,” said one of the campers I interviewed. “I don’t know how to get that experiment to work, but I can tell you 5 ways it won’t!” And that is a beautiful thing.

***

[1] NOT former, darling. Once a Queen, ALWAYS a Queen. We’re all Old Queens here.

[2] Yes, I asked her permission before using the name and she was “tickled” by the idea.

[3] Bribery is traditional and I like to think I elevated it to a new level. We set up tables in the square and did free science activities will all the kids and families who attended.

[4] Nope, not a typo. Slugs love rain and it the Pacific Northwest after all.

[5] Though sometimes we can go overboard on the qualifications.