Many practicing scientists, parents, and educators turn their hand to outreach as some point. They offer lab tours, give public lectures, host school day out workshops, coach after school robotics teams, and mentor students working on science fair projects, just to name a few.

Outreachers spend a their precious time, energy, and resources laser focused on the “what” of outreach, but few take a moment to think about the “why” of outreach.

I doubt you’ll be surprised to learn that I’m going to argue that the “why” is the most important part of outreach. Everything else should stem from your personal why. Here are just a few reasons why you might want to engage in science outreach:

To address inequities in STEM

To help my child enjoy science learning

To bolster my resume

To try out science teaching

To share my passion for science

All of these are good reasons to try outreach [1]. Your particular reason should inform how you choose to engage with outreach. What you shouldn’t do is go off and reinvent the wheel creating a program from ether because you think it’s expected or might be a cool thing to do. Outreach is cool, like a puppy or a hamster, and like those small mammals it’s a commitment and if you don’t nourish it, it will die. Of course a dead outreach program isn’t as sad as a dead pet, but you get the idea.

I’ve known many, many a scientists who have gotten involved in outreach because it seemed like a thing to do. They tried a few furlough day workshops for grade school kids, visited a classroom or two, or mentored a high school student for a summer. In most cases after a while, their careers and family life got busy and the outreach fell by the wayside. They enjoyed their time doing outreach, but aside from a few lines on the resume it never really amounted to anything.

Effective outreach has four elements: clear goals, appropriate theory, engaging activities, and evaluation. All of these things begin with WHY. Without why, you’re just goofing around. Hundreds if not thousands of outreach activities and programs have come and gone. Some were really good. Some are better off gone. We can’t really say much about almost any of them, though, because the people who ran them didn’t follow any process, document what they did, or evaluate their programs. They are, effectively, lost, never to be seen or learned from.

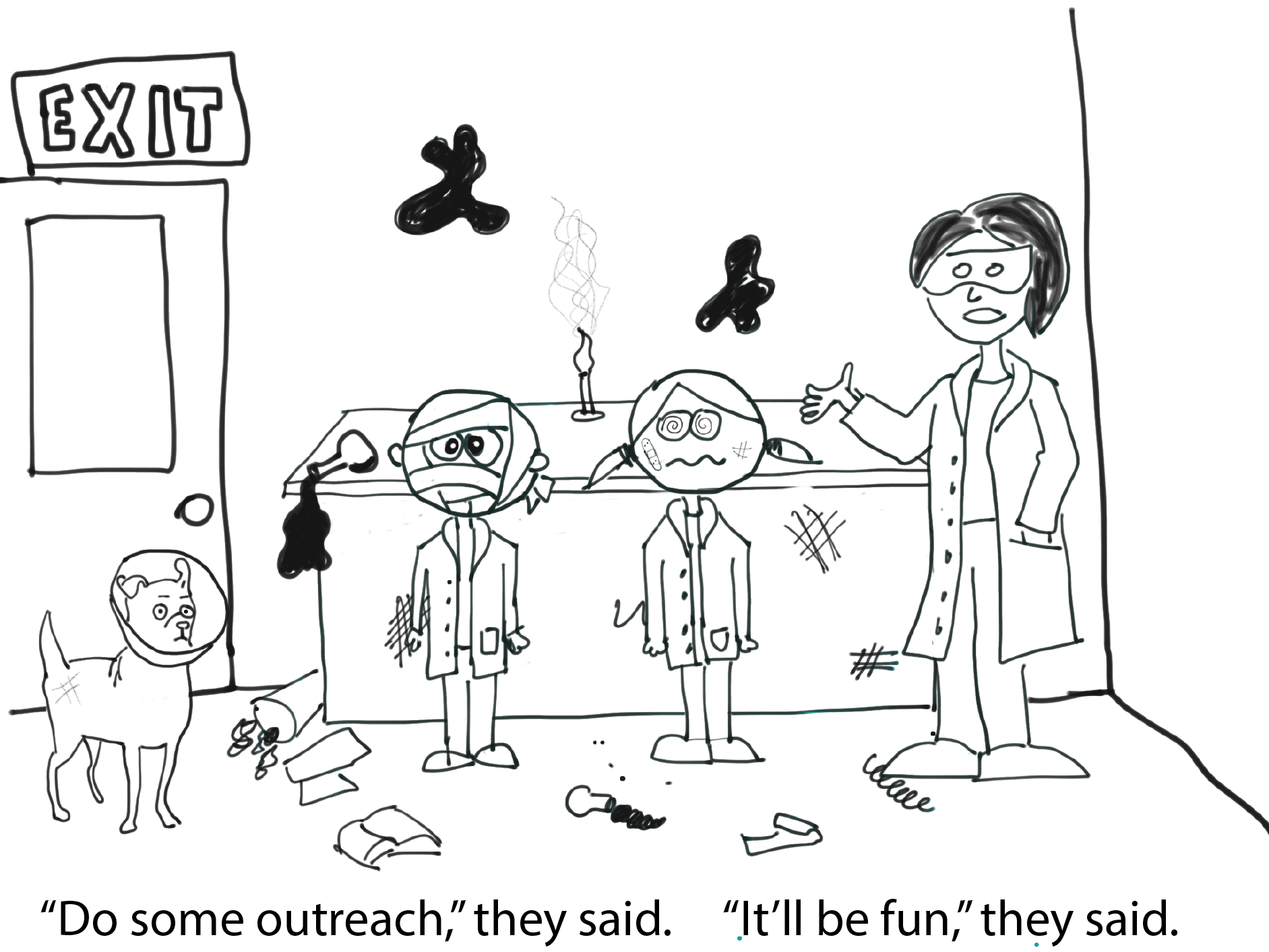

Image Credit: B. Todd

It’s sad to me to think of those programs, like the cats in Cats, forgotten, abandoned, eating from garbage cans with other sad, lonely abandoned outreach programs. Singing epic ballads for no one to hear [4]

Let this be a lesson so we may save future outreach programs from the dustbins of education history! To that end, here is Brandy’s, definitely not patented, short guide to starting with outreach.

Why do you want to do outreach?

Be honest! It’s going to be a lot easier to set reasonable goals and sustain (or see to completion) your outreach efforts if you have a clear idea of why you’re in it.

Look around to see if someone else is already doing something you could join in on.

Seriously, don’t reinvent the wheel. If you’re looking to try out informal teaching, if you want to share your passion for science, or if you want to pad your resume . . . I mean flesh out your experience. You can probably do that with an existing program. See what groups are doing science outreach around you. Find out what their goals and focus are. You may be able to slot into their programs and save yourself the hassle of handling administration and recruiting participants.

Set goals!

This applies to joining other groups or starting your own outreach program/event. What do you want to achieve? What is reasonable with the time and resources you have available? How might you go about measuring success (more about that in a bit)? Remember, in science, if you can’t measure it, it didn’t happen [3].

Align your goals to an appropriate theory and/or practice!

I can guarantee you, whatever it is you want to achieve, a lot of really smart people have already done work that can help you do better science outreach. Do you want to increase awareness of a particular career or discipline? Do a little searching on Google Scholar. What have people done before around career awareness? Where did they get the best bang for the buck? Lectures, mentoring, multimedia presentations, job shadowing? Do you want to increase participation in STEM by underrepresented groups? I’ll give you a hint. Developing new curriculum is probably not the best use of your time. Take a look at motivational theories. I’ll even say something blasphemous for an academic. Check out Wikipedia and Youtube while you’re hunting for theory that will be a good fit for you.

Operationalize

Yeah, that’s a 10 dollar word my spell checker doesn’t like. This means, take what you’ve learned in your investigation and set out some concrete practices you will use to meet those goals. Maybe even draw out a logic model!

Evaluate

Now that you have goals and practices, think about how you will evaluate what you’ve done. In my program we do a triangulated evaluation with self-reports from our participants, observations and fidelity rubrics completed by researchers, and measures of participant science affinity before and after camp. That’s a lot. You probably don’t need to go that far.

Why should you evaluate? Well don’t you want to know if worked? Don’t you want to get better at what you’re doing? We’re all science nerds here. What’s a science nerd without data?

Do it again! But better. Or don’t!

If you tried it and you liked it and you learned something, then you WIN! If you think you’d enjoy doing it again and that you can do it well, then GO FOR IT! If you hated it, then stop! Outreach should be fun for everyone. That means you to!

That’s it, Brandy’s tried and true method for doing outreach that works without reinventing the wheel.

It sounds like a lot, and it is. So by all means, borrow from what other people have shown works. Join in with experienced outreachers and learn from their past mistakes. And if you have a really great idea that no one else has tried, go for that as well! Just make sure to do your seven steps and keep revisiting them. Over time your goals and practices may need to change. That’s a good thing! It means you’re learning and growing as an outreacher.

Before I sign off I’ll give you an example of how this process can work for something simpler than a monster like the SPICE program.

The local chapter of Society of Physics Students wants to apply for a $500 grant from the national organization to do outreach so they get together to plan [5].

1) Why do we as student physicists want to do outreach?

Get experience teaching

Share our love of physics

Inspire young kids to love physics as well

2) Are there other groups doing outreach or events that we can join?

There are a number of other outreach groups on campus who’ve done similar outreach and there’s a science fair on campus each year that features fun science activity tables in addition to the science fair projects.

3) What are our goals?

The group decides to focus mostly on attracting kids to physics, but will also do some evaluation of how the teaching aspect went for the group members.

They decide to adapt 4 activities (gravity, forces, diffraction, aerodynamics) from the American Physical Society curriculum for k-8 age kids. They will test simplified versions of these activities out at a table at the science fair and then host their own Saturday physics event a month later. The fair will give them a chance to test and tweak the activities and to make connections to help recruit participants to the Saturday event.

4) Aligning goals and identifying theory

The group asks a STEM outreach practitioner from another program to come and talk to them about how to inspire young children to enjoy science. They learn about some key motivational theories and practices from the guest speaker.

5) Operationalize

They take what they’ve learned from the curriculum and consulting with other groups to develop an approach to how they will lead these lessons. They will use doublespeak to introduce complex science words. They will emphasize big concepts and relate those concepts back to kids lives. They will focus on leading kids to discover natural phenomena through inquiry.

6) Evaluation

They talk about their goals, look at some research done in education about measuring interest and come up with a short postcard sized survey they hand out to their Saturday workshop participants. They ask kids to report something interesting they learned. Ask them if they feel more likely now to want to learn physics. They have a similar card for parents to complete and ask if parents want to be added to an email listserv to get more info about future events. Afterwards, they poll the group. Were the events a valuable teaching experience? What would they do differently next time? Do they want to have a next time?

7) Future Plans

The group decides that outreach was more work than they realized, but they liked it and they learned a lot. They agree to make this an annual event, and let local summer camp programs know that a few of their members would be available to do short demonstrations or lead activities with those programs. They write up a 3 page report with color photos from the event and send it off to the national organization, along with their intent to keep participating in outreach.

This is a fairly basic example of doing outreach the right way. These students will be well positioned to do more outreach in the future and are armed with data that will help them show that the efforts were worthwhile and help them improve. Hopefully, over time the group will internalize good outreach practice and increase the sophistication of their evaluation methods. Maybe they’ll partner with an educational researcher or publish a paper in the society journal to share their lessons with other chapters.

And that’s what good outreach looks like. I’ve seen a lot of outreach in my time as an educator and it’s still pretty shocking how willing people are to sink time and effort into outreach without any clear plan. A lot. A lot of scientists think that because they are experts in their subject area that they will be good at sharing it with others. Very few scientists are naturally good at sharing science with the public. But there’s hope! Everyone can get better. Remember, you wouldn’t expect me to dive into quantum mechanics with only a social science background. So don’t expect to dive into organizing informal learning without at least a little planning and some new learning on your own part. The wonderful thing about science lovers, though, is the we LOVE learning new things.

Happy outreaching!

****

[1] Yes, it’s totally OK to be career minded!

[2] Psuedonym

[3] Of course if it happened it happened, but good luck proving it without DATA!

[4] No, I’ve never actually seen cats.

One great thing about grant funded outreach is that the sponsor will usually require you to do a lot of the things I’ve laid out above before they will give you money.